Lewis and Clark on the Great Plains A Natural History Chapter 4

Montana

Summary of Route and Major Biological Discoveries

On April 27, 1805, the expedition left the mouth of the Yellowstone River and probably passed the boundary of present-day Montana that same day. The courses of the Yellowstone and Missouri Rivers have changed greatly in the past two centuries, leaving room for some doubt as to the exact day the party reached what is now the eastern border of Montana. They very soon encountered large numbers of deer, elk, bison, wolves, and grizzly bears. They reached "Martha's River" (now the Big Muddy River) on April 29 and the "Porcupine River" (now the Poplar River) on May 3. The Milk River was reached on May 8 and the Musselshell on May 20. "Judith's River" (now the Judith River) was passed on May 29 and the mouth of "Maria's River" (now simply spelled the Marias River) on June 2, 1805.

A major geographic discovery, the Great Falls of the Missouri River, was reached on June 16, 1805. At that point a major portage was needed, and it was not until July 15 that the party was able to get under way again. Captain Clark and his small advance party reached the Three Forks region on July 25,where the Jefferson, Madison, and Gallatin Rivers (all named by Lewis and Clark) merge to form the Missouri. It was also near here that Sacagawea had been captured five years previously. At Three Forks the expedition had reached an elevation of slightly more than 4,000 feet and was at the very western edge of the Great Plains. The rest of the group arrived the 17th, and after three more days of local exploration they set off again. Following the westernmost branch (Jefferson River) upstream, the expedition soon was in the heart of the Rocky Mountains and about to cross the Continental Divide.

The route of the return trip across Montana is complicated by the fact that the expedition split into several parties after crossing the Rocky Mountains at Lolo Pass, west of present-day Missoula. From Travelers' Rest camp (about 20 miles south of Missoula) Captain Clark and a group of 20 men, plus Sacagawea and her son, began traveling southward on July 3, progressively making their way past the sites of present-day Hamilton and Jackson. On July 8 they reached the Beaverhead River somewhat above the location of present-day Dillon, where they found their cache of supplies as well as their canoes. From there they moved downstream to Three Forks, arriving July 13, 1806. Ten members of Captain Clark's group were then sent via canoes from Three Forks to Great Falls, to begin the arduous portage around the falls and rapids.

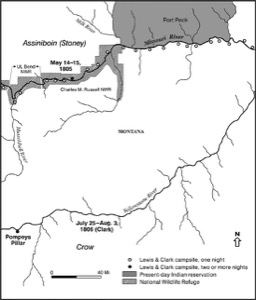

Map 5. Route of Lewis and Clark in Eastern Montana

Outward Route Schedule: April 27 to July 27, 1805

Return Schedule: July 7 to August 3 (Clark) or August 7 (Lewis), 1806

River Distance: Montana-North Dakota border to Three Forks, 945 river miles, according to Lewis and Clark. Because of recent impoundments, present-day river distances are now substantially less than the original distances calculated by Lewis and Clark.

Map of route of Lewis and Clark in Eastern Montana

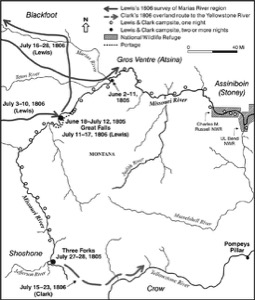

Map 6. Route of Lewis and Clark in Western Montana as Far as Three Forks

Outward Route Schedule: April 27 to July 27, 1805

Return Schedule: July 7 to August 3 (Clark) and August 7 (Lewis), 1806

River Distance: Montana-North Dakota border to Three Forks, 945 river miles, according to Lewis and Clark. Because of recent impoundments, present-day river distances are now substantially less than the original distances calculated by Lewis and Clark.

Map of route of Lewis and Clark in Western Montana as Far as Three Forks

Captain Clark and his remaining 12-person contingent (10 men plus Sacagawea and her 17-month-old son, Baptiste) and their horses moved overland across Bozeman Pass and reached the upper Yellowstone ("Rochejhone") River near the present site of Livingston on July 15, 1806. There the trees were not large enough to make canoes, so they continued downstream. At the approximate site of present-day Columbus the group stopped long enough to manufacture two dugout canoes from cottonwoods and then resumed water travel on July 24. They gradually made their way down the Yellowstone, making a short stop on July 25 at a sandstone promontory that Clark named "Pompy's Tower" in honor of Sacagawea's son, whom Clark had nicknamed Pompy. There Captain Clark inscribed his own name and the date. In that general vicinity they saw a large herd of bighorns as well as flocks of geese and pigeons. They arrived at the mouth of the Yellowstone on August 3, 1806, thus finally leaving present-day eastern Montana and again passing into what is now western North Dakota.

From Travelers' Rest camp, Captain Lewis and his group of nine men (and five guides) independently set forth in a northeasterly direction on July 3, 1806, for Great Falls, arriving at the river after a hard march of eight days. He left six of his party at Great Falls to assist Clark's ten-man contingent with the downstream portaging, and with his remaining three handpicked men headed on July 16 for a brief reconnaissance of the Marias ("Maria's") River. On their way north, they sequentially crossed the Sun River ("Medicine River") and the Teton River. After reaching the Marias, Lewis doggedly followed it northwest to a point about 20 miles west of present-day Cut Bank, along a northern tributary, Cut Bank Creek. He was searching for the northernmost limits of the Missouri's drainage, and thus the possible northernmost legal limits of the Louisiana Purchase. By July 22 he was within sight of the Rocky Mountains, but the river had still not turned north, and several days of bad weather had made it impossible for him to establish his exact location. After turning back south and crossing Two Medicine River (the south fork of Maria's River in Lewis's terminology), the exploration ended abruptly on July 27 when eight Piegan Blackfoot men, with whom they had held a peaceful council the day before, tried to steal the group's guns and horses. In the resulting fight one Blackfoot man was killed and another was evidently fatally wounded. Lewis himself was very narrowly missed by a musket ball. Lewis and his men quickly retreated and again reached the Missouri River near the present site of Virgelle on July 28. The site of this harrowing encounter is on private land about 15 miles northeast of present-day Valier.

The group of six men who had been left by Captain Lewis to negotiate the Great Falls portage was soon met by the ten others who had been sent downstream by Captain Clark from Three Forks to help with the portaging. After negotiating the Great Falls portage, the 16 men continued downstream. By the greatest of good luck, they encountered Lewis and his three-man party just as they were returning to the mouth of the Marias River on July 28. The reunited group of 20 men then descended the Missouri under the leadership of Captain Lewis, reaching the mouth of the Yellowstone River and arriving at the approximate present-day boundary of North Dakota on August 7, 1806, only four days behind Captain Clark's group that had come via the Yellowstone. Thus the last members of the Corps of Discovery departed from what is now Montana.

Mammals

-

Bighorn Sheep Ovis canadensis auduboni

In Montana, bighorns were reported from at least 15 locations, and at least 35 were killed during the entire expedition. As noted previously, bighorn sheep were first observed at the mouth of the Yellowstone River in extreme western North Dakota and were subsequently seen as far west as the Beaverhead Mountains in Montana. In one location below the mouth of the Marias River the party killed nine sheep in a single day. None was seen along the upper Marias River by Captain Lewis. The bighorn was formally described and named in 1804. The species still ranges widely in the American and Canadian Rocky Mountains, and the poorly characterized race O. c. auduboni historically inhabited the upper Great Plains from Nebraska to North Dakota at the time of the Lewis and Clark expedition. It was first distinguished subspecifically from the more widespread Rocky Mountain form in 1901. The last state record for native bighorns in North Dakota was in 1905, for South Dakota in about 1915, and for Nebraska in 1918. Reintroduced bighorns of the nearly identical Rocky Mountain race now occur in Nebraska's Pine Ridge and Wildcat Hills, in South Dakota's Black Hills and Badlands National Park, and in North Dakota's Theodore Roosevelt National Park.

-

Bison Bison bison

Bison were reported in present-day Montana from at least 33 locations, from the North Dakota boundary west up the Missouri Valley almost to Great Falls, along the Sun and Marias Rivers, and along the Yellowstone Valley from about present-day Billings to the North Dakota boundary. After the great bison slaughter of the middle and late nineteenth century, when more than 40 million animals were destroyed, the only remaining bison south of Canada were a few hundred individuals that were protected in Yellowstone National Park. From these and from some small captive herds the present population of several hundred thousand bison has been produced.

-

Bushy-tailed Woodrat Neotoma cinerea FIG. 31

The bushy-tailed woodrat was first accurately described by Lewis and Clark, but the species was not formally named until 1815. They encountered it in the vicinity of Great Falls on July 2, 1805, and captured a live specimen. Captain Lewis described it with care, noting that he had often seen the animals' dens in cliff and tree hollows, and that they often eat the fruits and seeds of the prickly pear (Opuntia sp.). Woodrats, more generally known as "packrats," accumulate caches of food items such as cactus fruits, acorns, pine cones, bones, and even inedible objects such as small plastic items and other miscellaneous "treasures" that they happen to find in the vicinities of their nests. It is now known that bushy-tailed woodrats extend east into the western Dakotas, and a few decades after Lewis and Clark's expedition Prince Maximilian found them to be present at both Fort Clark and Fort Union.

-

(Columbian Ground Squirrel Spermophilus columbianus)

Lewis and Clark made many observations of the Columbian ground squirrel on the western slope of the Rockies, but only a few apply to the extreme western Great Plains. In July of 1806 Clark encountered this species in the upper Bitterroot Valley, and during Lewis's independent survey of the Marias River region during the same month he encountered these animals east of present-day Missoula and on the Cut Bank branch of the Marias River. The Columbian ground squirrel was first described by Lewis and Clark on the basis of specimens they obtained in Oregon, but it was not given a formal Latin name until 1815. This species is primarily associated geographically with the Columbia River Basin much farther to the west.

-

Coyote Canis latrans

At a minimum, coyotes were encountered near Wolf Point and on the upper Marias River in Montana, but they were evidently much less common than gray wolves there and were only rarely mentioned. They became much more common everywhere after the disappearance of gray wolves from the Great Plains, and have gradually extended their range eastward to the Atlantic coast. In spite of massive poisoning and other control efforts, the coyote has thrived better than any other native American dog or cat.

-

Elk Cervus elaphus

In Montana, elk were reported from at least 37 locations, from around the present-day North Dakota boundary west along the Missouri Valley to its Three Forks headwaters, in the mountains to the Bitterroot Valley, and along the entire Yellowstone Valley. They were also seen along the Sun River and in the Marias River valley near present-day Shelby. They were especially numerous along the Yellowstone River, where herds of up to 200 were apparently common. They are still locally common in Montana but are mainly confined to forested areas and sanctuaries. Elk were eliminated from Nebraska and North Dakota by the early 1880s and from South Dakota by 1888. Restoration efforts have occurred in all three states, and small, mostly confined herds exist in them.

-

Gray Wolf Canis lupus

Wolves were especially common in Montana, where they were reported from at least 17 locations, and the herds of bison were regularly "attended by their shepherds the wolves." Near the mouth of the Sun ("Medicine") River Captain Lewis noted that most of the wolves seen around a bison carcass "were of the large kind." Gray wolves were eventually extirpated from Montana, but recent releases in the Yellowstone Park area have restored them to the state's faunal list. They have since been seen as far south and east as Wyoming's Wind River Range.

-

Grizzly Bear Ursus arctos

During the 1805 ascent up the Missouri grizzlies were seen by expedition members at no fewer than 17 locations, and Lewis also mentioned them at three locations during his survey of the Marias River valley. Clark likewise saw them at least twice as he traveled down the Yellowstone Valley. Lewis and Clark referred to grizzly bears under various names, including the "white bear," "brown bear," and "grizly bear." Captain Lewis eventually concluded that all these color variants were "of the same species only differing in color from age or more properly from the same natural cause than many other anamals of the same family differ in coulur." The grizzly bear was not formally described and named as a distinct species ("Ursus ferox") until 1815, based on the descriptions and specimens of Lewis and Clark. Raymond Burroughs calculated that at least 43 grizzly bears were killed over the entire expedition period, most of them in Montana. Twenty three were killed between the mouth of the Yellowstone and Three Forks, Montana. Ten were killed in the vicinity of Great Falls alone, and 14 were killed during the separate return trips of Lewis and Clark down the Yellowstone and Missouri Rivers of Montana. Every shooting of a grizzly was a highly risky undertaking. One enormous 600-pound male required ten shots to bring it down. On May 14 six men set out to kill a grizzly bear. Although all six lead balls hit the bear, it attacked, and only after two more bullets struck it, one in the head, did it finally collapse, just before reaching its closest human target. Montana now has one of the very few remaining populations of grizzly bears south of Canada, with perhaps 500 to 1,000 surviving in the northern Rockies of the United States and Canada, centering on the Glacier-Banff-Jasper ecosystem. There are a few left in the Yellowstone Park ecosystem, and they range east and south locally to Wyoming's Wind River Range.

-

(Moose Alces alces)

Several "moose deer" were reportedly seen on May 10, 1805, in present-day Dawson County, Montana, according to Sergeant Ordway's journal. No other information was provided, and the identification seems rather unlikely, given this geographic location in the high plains of eastern Montana, well away from typical moose habitat.

-

Mountain Lion Puma concolor

A few encounters with mountain lions occurred while the expedition was still on the Great Plains. On May 16, between the Milk and Musselshell Rivers, a mountain lion ("panther") was shot and wounded, but it escaped. One was killed on the Jefferson River on August 3, 1805, and a few days later three deerskins disappeared from camp and were judged to have been stolen by a mountain lion. In spite of continuous persecution ever since, mountain lions have somehow survived in the Rocky Mountains and Black Hills regions. Occasionally stray animals still wander east into Nebraska and eastern South Dakota and North Dakota, usually with fatal results to the cats. Their prime prey, mule deer and white-tailed deer, have vastly increased in the absence of large predators such as wolves and mountain lions, but the increased human population has had little tolerance for mountain lions, and most that stray into the Great Plains are quickly killed.

-

Mule Deer Odocoileus hemionus

and White-tailed Deer Odocoileus virginianus

Deer of unspecified species were reported by Lewis and Clark from at least 33 Montana locations, in addition to nine reports specifically of mule deer and two of white-tailed deer. White-tailed deer were seen west along the Missouri River to about Wolf Point, and mule deer from that point west up the Missouri Valley to the Rocky Mountains. In recent years white-tailed deer have been increasing relative to mule deer in the western Great Plains and are now as common as mule deer at least as far west as western North Dakota and western Nebraska.

-

Northern Pocket Gopher Thomomys talpoides

Although Lewis and Clark did not actually observe these reclusive animals, Captain Lewis described their characteristic tunnels and mounds, so to a limited degree he may be credited with discovering the species. The northern pocket gopher was not formally named until 1828.

-

Northern River Otter Lontra canadensis

In Montana, otters were reported by Lewis and Clark from at least 15 locations; they were especially numerous between Great Falls and the vicinity of Three Forks, where water clarity and associated fishing opportunities were certainly better than were typical farther downstream. At the time of the Lewis and Clark expedition otter pelts were not nearly as highly valued as beaver pelts, and little attention was paid to them. However, Native Americans prized their fur, which was used for ceremonial paraphernalia. Medicine sacks were also made from their skins.

-

Pronghorn Antilocapra americana

Pronghorns were reported from at least 47 Montana locations, from approximately the North Dakota boundary up the Missouri Valley to a point beyond present-day Dillon, in the Sun and Marias Valleys, and down the Yellowstone Valley from present-day Livingston to the mouth of the Bighorn River.

-

Red Fox Vulpes vulpes

In Montana, red foxes were reported from at least three locations, as compared with only one coyote reference and 17 locations where wolves were mentioned. Red foxes and swift foxes have both generally suffered in recent decades, inasmuch as these small foxes are regularly killed by coyotes. Coyotes have increased in the Great Plains because their populations are no longer being controlled by gray wolves.

-

Swift Fox Vulpes velox FIG. 32

The swift fox was first recognized as a distinct species by Lewis and Clark but was not formally described and scientifically named until 1823. It was first encountered on July 6, 1805, in the vicinity of Great Falls. At that time Captain Lewis referred to the animal as a "remarkable small fox." Two days later one was shot, and it was carefully described by Lewis. He noted its remarkably long claws, and later (July 26) mentioned the black tip of its tail, another distinguishing features of the species. This high plains species is now barely surviving in Nebraska, the Dakotas, and eastern Montana, with very few recent records for any of these states. There are only two North Dakota records since 1976 (Mercer and Golden Valley Counties), and four southwestern South Dakota counties have recent records. There may also be some swift foxes left in the nearby Oglala National Grassland of northwestern Nebraska and in Nebraska's Box Butte County, where some were photographed in 2001. Perhaps some also survive in the extreme southwestern counties of Nebraska near the Pawnee National Grassland of adjacent Colorado, where they are known to occur. Swift foxes are easily trapped, and in most areas have lost prairie dogs as part of their food base.

-

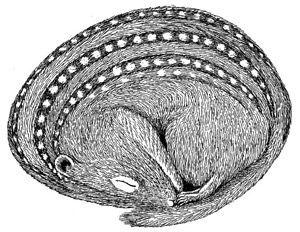

Thirteen-lined Ground Squirrel Spermophilus tridecemlineatus

FIG. 33

This common ground squirrel of the northern plains was not mentioned until the expedition had entered Montana, even through the species is extremely common in the Dakotas and Nebraska. It was first noted near the Great Falls on July 4, 1805, when Captain Lewis obtained a live specimen and carefully described it. The thirteen-lined ground squirrel was not formally described and named until 1821. It is still one of the most commonly seen and widespread rodents of the northern plains, and is a major food for coyotes, badgers, and other grassland predators. Like other ground squirrels, it is dormant for more than half of the year, which may reduce predation levels.

Birds

-

American Avocet Recurvirostra americana

There is no doubt as to the identity of the bird shot on May 1, 1805, about 75 miles above the mouth of the Yellowstone River. It was carefully described by Captain Lewis, who incorrectly believed it new to science. He called it the "Missouri plover." Avocets are still fairly widespread in the more alkaline wetlands of western North America; their uniquely recurved bills are mainly used for extracting small invertebrates from the surface of water by a kind of lateral scything action.

-

American Goldfinch Carduelis tristis

Lewis also mentions seeing goldfinches among the birds singing along the Marias River in Montana on June 8, 1805. He was apparently quite familiar with this widespread woodland-and-edge species and gave it no special attention. Goldfinch populations have declined significantly in the past four decades.

-

Belted Kingfisher Ceryle alcyon

In the expedition's Meteorological Register of May 23, 1805, it was noted that a kingfisher was first seen seasonally near present-day Fort Peck. It was also seen near Great Falls (July 11-13, 1805). This distinctive bird is still common along relatively clear rivers supporting small fishes. Belted kingfisher populations have declined significantly in North America during the last four decades, probably as a result of increased levels of water pollution.

-

Brown-headed Cowbird Molothrus ater

and Brewer's Blackbird Euphagus cyanocephalus

Few specific notes were made on these presumably common and probably widespread species, which are adapted to forage at the feet of large ungulates such as bison. In the expedition's Meteorological Register of May 17, 1805, it was noted that "large and small blackbirds" had returned to eastern Montana. Elliott Coues identified these as most probably brown-headed cowbirds and Brewer's blackbirds. Probable cowbirds were also seen near Great Falls (July 11- 13, 1805, and July 11, 1806), and this species (referred to by the explorers as the "buffalo-pecker") must have regularly associated with bison before domestic cattle appeared on the Great Plains. Cowbird populations are now declining nationally, but they still pose a serious threat to native songbirds because of their parasitic nesting behavior. Brewer's blackbird populations have also declined significantly rangewide.

-

Cliff Swallow Petrochelidon pyrrhonota

On May 31, 1805, in what is now Chouteau County, Montana, Lewis saw a group of what he called "small martin" building globular nests of clay on a cliff wall. These could only have been cliff swallows, which now widely nest on vertical manmade structures, such as the sides of concrete bridges.

-

Common Nighthawk Chordeiles minor

On June 30, 1805, near Great Falls, Montana, Captain Lewis shot a bird he identified as a species of goatsucker, reporting that it was identical to those of the Atlantic states, "where it is called the large goat-sucker or night hawk." Nighthawks, whip-poor-wills, and poorwills are aerial insect-eaters; their extremely large mouths are responsible for their colorful if erroneous vernacular name "goatsuckers." Common nighthawk populations have declined significantly in North America during the last four decades, as have other goatsuckers.

-

Eastern Kingbird Tyrannus tyrannus

or Western Kingbird Tyrannus verticalis

Few specific notes were made on these rather conspicuous songbird species, and not enough information was offered to distinguish which kingbird species was seen. In the expedition's Meteorological Register of May 25, 1805, it was noted that the "king-bird or bee-martin" had returned seasonally to the vicinity of the mouth of the Musselshell River. Kingbirds are rather late spring arrivals in the northern United States, as they winter in tropical America. The eastern species is more likely to have been seen than the western, since the eastern would have been the one familiar to the explorers and would not have attracted special attention. Also, it is more often found closer to water than the more arid-adapted western species. Kingbirds of undetermined species were also noted on June 10, 1805, near the mouth of the Marias River, and on August 2, 1806, near present-day Missoula. The eastern kingbird's rangewide population has declined significantly during the past four decades.

-

Greater Sage-grouse Centrocercus urophasianus FIG. 34

One of the species definitely discovered by Lewis and Clark is this large sage-adapted grouse. It was first seen on June 5, 1805, near the Marias River in Montana, when an attempt to kill one was unsuccessful. Others were seen at Lemhi Pass in the Beaverhead Mountains on August 12 of that year, but it was not until October 17 that several were actually shot. Both Lewis and Clark provided detailed descriptions of the species, Clark calling it the "prarie cock" and Lewis the "cock of the plains." Lewis also first described the species' unusual saclike gizzard, describing it as more like a "maw" (crop) than a typical muscular grinding organ. He said this grouse feeds almost entirely on the "pulpy leafed thorn," presumably confusing the relatively inedible black greasewood with the bird's actual primary (almost sole) food, the highly nutritious leaves of big sagebrush (Artemisia tridentata). John J. Audubon used Lewis's' suggested name "cock of the plains" when he painted the species about three decades later. Greater sage-grouse populations have plummeted in recent decades, as the West's once-vast areas of native sagebrush have been progressively cleared.

-

Lewis's Woodpecker Melanerpes lewis FIG. 35

One of the major ornithological discoveries of the expedition was Captain Lewis's discovery of the woodpecker that now bears his name. On July 20, 1805, along Prickly Pear Creek and near present-day Helena, Montana, Lewis first saw a "black woodpecker (or crow)." He judged it to be about the size of a flicker but as black as a crow. He was not able to obtain a specimen until May of 1806, when in Idaho the expedition members "killed and preserved several." He then provided a highly detailed description of the bird, and at least one of the preserved specimens made its way back east, where it eventually ended up in the hands of Charles W. Peale, curator of the Philadelphia Museum housed in Independence Hall. The specimen that Alexander Wilson used to illustrate the species for the first time was one of those collected by Lewis and Clark, and it was named "Lewis's woodpecker." Wilson's original sketches of this woodpecker and of Clark's nutcracker (Nucifraga columbiana), similarly named after Captain Clark, are still present in the Academy of Natural Sciences of Philadelphia. Like the red-headed woodpecker, the Lewis's woodpecker is distinctly migratory and often occurs well away from dense woods. Its population numbers have not changed significantly in the past four decades.

-

Loggerhead Shrike Lanius ludovicianus

Captain Lewis discovered the nest and eggs of the loggerhead shrike on June 10, 1805, near the mouth of the Marias River in Montana. He described it in considerable detail, thinking the species might be new to science. However, it later was recognized as an undescribed subspecies of an already known species. Lewis noted the shrike's hawklike claws and judged it to be a predator of insects. It is now known to prey also on a wide variety of animals, including both small mammals and birds. It is characteristic of open, often arid, country. Loggerhead shrike populations have declined significantly in North America during the last four decades.

-

Mallard Anas platyrhynchos

Mallards, usually called "duckinmallards" by the explorers, were often seen but generally not distinguished from other duck species. However, they were mentioned specifically as present in the vicinity of Three Forks, Montana, on July 29, 1805, and again on August 2 on the Jefferson River above Three Forks. Mallard populations have probably increased substantially during the past century as a result of wildlife management programs.

-

McCown's Longspur Calcarius mccownii FIG. 36

One June 4, 1805, near the mouth of the Marias River in Montana, Lewis saw a sparrow-sized bird taking flight, singing, and then dropping back to earth. His detailed description leaves little doubt that he had observed the McCown's longspur in its aerial territorial display. This species was not officially described and named until 1851,more than four decades later. It is a typical species of arid shortgrass prairies, and its population appears to be declining rangewide.

-

Merganser Mergus sp.

Lewis and Clark's "red-headed fishing duck" was judged by Elliott Coues to be the red-breasted merganser (Mergus serrator). This description applies only to female or immature male mergansers and would also fit the common merganser (Mergus merganser). Indeed, the common merganser is the typical breeding species of this region. Mergansers were observed on June 21, 1805, in the vicinity of Great Falls, as well as near the present-day locations of Helena (July 20, 1805), Townsend (July 24, 1805), and Whitehall (August 2, 1805). They are largely confined to fairly clear streams that permit visual hunting for fish, and common mergansers still breed locally in western Montana.

-

Mourning Dove Zenaida macroura

Few specific notes were made on this common and well-known species. In the expedition's Meteorological Register of May 8, 1805, it was noted that the "turtle dove" had returned to northeastern Montana, near Fort Peck. It was seen near the mouth of the Marias River on June 8, 1805. On the return trip of 1806 it was observed near the present-day locations of Missoula and Billings, near Great Falls, and on the upper Marias River. Mourning dove populations have declined significantly in North America during the last four decades; they are a highly adaptable but heavily hunted species.

-

Osprey Pandion haliaetus

The "white-headed fishing hawk" was seen by Captain Lewis on August 9, 1805, near present-day Grayling, Montana. Lewis also noted that it had not been seen below the mouth of the Yellowstone River. He was clearly already familiar with this wide-ranging and fish-eating species, which favors hunting in clear water. Its population trends have been volatile, as like the bald eagle and other fish-eating birds it was seriously affected by pesticide poisoning during the mid- twentieth century.

-

(Pine Siskin Carduelis pinus)

Captain Lewis mentioned seeing the "linnet" on the Marias River on June 8, 1805, a bird name that has sometimes been associated with the pine siskin. However, several other small finches have historically been called linnets, and Lewis's identification seems rather unlikely given the location and date.

-

Red-headed Woodpecker Melanerpes erythrocephalus

Few notes were made on this common and widespread species. In the expedition's Meteorological Register of May 28, 1805, it was noted that a "small black and white woodpecker with a red head, the same which is common in the Atlantic States" was seen in northern Montana near the mouth of the Judith River. It was also seen July 16, 1806, near Great Falls and near present-day Fort Peck on August 3, 1806. Unlike some similar-sized woodpeckers such as the downy and hairy, this is a seasonally migratory species, at least in the northern states. Its rangewide population has declined significantly in the past four decades.

-

Sandhill Crane Grus canadensis

The first mention of sandhill cranes by Lewis came on July 15, 1805, in the vicinity of the Gates of the Rocky Mountains, Montana, where several examples of the "large brown or Sandhill crain" were seen leading young. A living young bird was also brought into camp on July 19, 1805, near Three Forks, Montana. Lewis eventually released it. Greater sandhill cranes (Grus canadensis tabida) continue to survive in the northern Rocky Mountain region and have been increasing both regionally and nationally in recent decades as a result of long-term protection.

-

Upland Sandpiper Bartramia longicauda

or Mountain Plover Charadrius montanus

On July 22, 1805, Captain Lewis reported seeing "a species of small curlooe of a brown color" at present-day Canyon Ferry, Montana. This bird was tentatively identified by Rueben Thwaites as a mountain plover, but Elliott Coues instead believed that it might have been an upland sandpiper. Either species would be geographically possible, but the sandpiper, which is somewhat more curlewlike than the plover and is more widespread, would seem the more likely possibility. Descriptive terms such as curlew (spelled variously) and plover were evidently used rather indiscriminately for shorebirds by expedition members, with curlew perhaps usually applied to the longer-billed or larger species. Too little information is available to make an informed guess as to the identity of this particular bird. The mountain plover's population has declined to the point that it is now a federally endangered species, whereas the population of the upland sandpiper has increased slightly during the past four decades, one of the very few grassland-adapted bird species that has shown this trend.

-

Willet Catoptrophorus semipalmatus

This species was collected on May 9, 1805, at the site of present-day Fort Peck, Montana. Captain Lewis described this bird with some care and detail, incorrectly thinking it might be new to science, and he especially noted its resemblance to the "large grey plover" or "Jack Curloo." He described the bird's wings as white, tipped with black, making identification of this distinctive species fairly certain. Like avocets, willets are still fairly common in the more alkaline wetlands of western North America.

Reptiles

-

(Painted turtle Chrysemys picta)

"Water terrepens" were noted in the vicinity of Great Falls, Montana, on June 25, 1805. Their specific identity is in some doubt, but this might be a reference to the common and geographically widespread painted turtle.

-

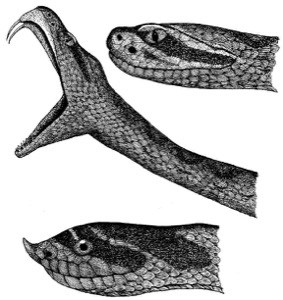

Prairie (Western) Rattlesnake Crotalus viridis FIG. 37

Many encounters with rattlesnakes were reported by the expedition; one of the earliest that certainly involved the prairie rattlesnake occurred May 17, 1805, near the mouth of the Yellowstone River. Rattlesnakes were also encountered in Missouri, Nebraska (in present-day Washington and Boyd Counties), and South Dakota (near the White River). Of these, the Missouri and southern Nebraska locations may possibly have involved the relatively large and more dangerous timber rattlesnakes (Crotalus horridus), but the later encounters on the high plains of the Dakotas and Montana most likely involved the somewhat smaller and then still-undescribed western or prairie rattler. Expedition members later encountered rattlesnakes at least a dozen times on the plains of Montana, including several near escapes from being bitten. The western rattlesnake was not formally described and given a Latin name until 1818.

-

Softshell Turtle Apalone sp.

Softshell turtles, probably representing the spiny softshell (A. spinifera),were mentioned as seen on the Missouri River of Montana above the mouth of the Musselshell River on May 26, 1805, and also on the Yellowstone River on July 19, 1806. These are fairly common river-dwelling turtles that were probably already well known to Captain Lewis and thus not considered worthy of special attention.

-

Western (Wandering) Garter Snake Thamnophis elegans vagrans

On July 24, 1804, Captain Lewis closely examined some snakes seen near Three Forks, Montana, and found them to be "much like the garter snake of our country." They have been tentatively identified by Elliott Coues as western garter snakes of the race vagrans.

-

Western Hognose Snake Heterodon nasicus FIG. 37

A snake that Captain Lewis found and described on July 23, 1805, near present-day Townsend, Montana, most probably can be referred to this species. The western hognose snake was not formally described until 1852, so Lewis should be credited with discovering the species. It is mildly venomous and has a somewhat frightening, cobralike defensive display. Its distinctive upturned snout is used for digging in sand, where it searches for toads and other prey.

Fish

-

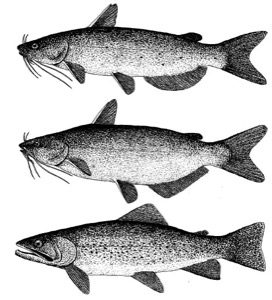

Channel Catfish Ictalurus punctatus

and Blue Catfish Ictalurus furcatus FIG. 38

Catfish, most probably including both the channel and blue catfish, were caught and eaten at various points along the Missouri River, from Missouri to Montana. The channel catfish ranges upstream to Montana, and the blue catfish to the Dakotas. "White catfish" were caught in numbers, and one of the party's major Nebraska campsites (July 22-26, 1804, near present-day Lake Manawa) was named "White Catfish camp" because of the several large catfish caught there. Channel catfish and blue catfish both occur in this region and both closely resemble the white catfish (Ictalurus catus) of eastern North America. However, the blue catfish is on average considerably larger than the channel catfish, the largest known examples exceeding 100 pounds, whereas channel catfish rarely reach 30 pounds. Nine catfish caught near the mouth of the Vermillion River on August 25, 1804, collectively weighed nearly 300 pounds, which would strongly suggest that they were blue catfish.

-

Cutthroat Trout Salmo (Onchorhynchus) clarki FIG. 38

This newly discovered species, later named in honor of Captain Clark, was first caught on June 13, 1805, in the vicinity of Great Falls. The species' detailed description by Captain Lewis leaves no doubt as to its identity.

-

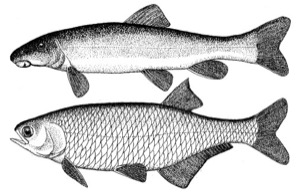

Goldeye Hiodon alosoides FIG. 39

Fish identified by Elliott Coues as goldeye, a previously unknown species, were caught on June 11, 1805, above the mouth of the Marias River. They were described by Captain Lewis as resembling the "hickory shad" (the gizzard shad, Dorosoma) or the "oldwife" (the alewife, Alosa), except for their large eyes and long teeth. The goldeye is predatory and does have unusually large, golden eyes and abundant teeth. It is also the only species of the mooneye family (Hiodontidae) occurring in Montana. The goldeye was first formally described and named in 1819, but Lewis probably should be given credit for its discovery.

-

Sauger Stizostedion canadensis

Fish caught on the Missouri River above the mouth of the Marias River were identified by Elliott Coues as saugers, a species then already known to science. More recently, Ken Walcheck has suggested on the basis of their described tooth structure that this species might instead have been the flathead chub (Hybopsis gracilis), a much smaller species of fish.

-

Suckers Catastomus and Prosopium spp. FIG. 39

The suckers that were caught in the Missouri River of Montana by the expedition were identified by Elliott Coues as probably being the common northern (or longnose) sucker (Catastomus catostomus), a species then already known to science. One caught on the Yellowstone River on July 16, 1806, was identified by Coues as representing the then-undescribed mountain sucker (Prosopium williamsoni). The mountain sucker was not described until 1892, with specimens from western Montana. Both of these suckers are known to occur in the Yellowstone River.

Plants

-

Black Greasewood Sarcobatus vermiculatus

This shrub was the "pulpy leaf thorn" described by Lewis and Clark. Theirs is a good description, inasmuch as its leaves are fleshy and its rigid branches somewhat spiny. It is a widespread perennial shrub in alkaline soils, with leaves that are highly toxic to many animals but may be eaten during winter as an emergency food by some wild ungulates. Captain Lewis believed, incorrectly, that the greater sage-grouse also regularly consumed this plant's leaves. Native Americans sharpened the strong branches of this shrub and used them as digging tools. Collected July 20, 1806, in present-day Toole County, Montana.

-

Blue Flax Linum lewisii

This perennial plant, named in honor of Captain Lewis by Frederick Pursh, was collected July 9, 1806, perhaps in Beaverhead County, Montana. Lewis recognized that the stem of this plant produces strong fibers that might make "excellent flax." It was evidently used as such by Native Americans. A newly discovered species.

-

Eastern Cottonwood Populus deltoides

The herbarium specimen was presumably obtained in North or South Dakota if the indefinite date (August 1806) is correct. Cottonwood leaves and bark contain salicilin and populin, both precursors to the medicinally important aspirin. Not surprisingly, teas made from the bark of cottonwood were used by Native Americans for various ailments. Cottonwood trees were also extremely important to the success of the entire expedition, inasmuch as their fairly soft wood and the large size of the mature trees occurring along river edges made them excellent candidates for manufacturing dugout canoes. Ten of the 15 dugout canoes the expedition members constructed were made from cottonwoods, the others from ponderosa pine (Pinus ponderosa).

-

Gumbo Evening Primrose Oenothera caespitosa

This is a widespread perennial forb that is typical of badland soils and other nearly barren grounds. The roots of this and related species were used as external poultices for bruises, and the boiled root was used for a wide variety of ailments. The oils present in the seeds (such as linolenic acid) are also known to have physiological effects. Collected July 17, 1806, in present-day Cascade County, Montana. A newly discovered species.

-

Needle-and-thread (Porcupine) Grass Stipa comata

This species and wild rice are the only grasses represented in the Great Plains collections of Lewis and Clark, and surprisingly few other grasses were collected farther west. It is a common perennial species of mixed-grass prairies. Collected July 8, 1806, in Lewis and Clark County or Beaverhead County, Montana.

-

Red False (Scarlet Globe) Mallow Sphaeralcea coccinea

This is a widespread perennial forb. The Blackfoot used a paste made from chewing the plant stems and leaves as an external medicine for burns and sores. The Lakotas similarly made a paste to rub over their hands and arms, thus seemingly making them immune to the effects of scalding water. The "contrary medicine men" of the Lakotas used this purported protective trait to impress onlookers and encourage faith in their apparent special powers. Collected July 20, 1806, probably in present-day Toole County, Montana. A newly discovered species.

-

Snow-on-the-Mountain Euphorbia marginata

This is a widespread perennial forb on dry grasslands. Its leaves are somewhat poisonous, but they were used by the Dakotas as a basis for medicinal tea, which was used to treat mothers producing insufficient milk, and its crushed leaves were also used in warm water to make a kind of liniment. However, exposure of the skin to the milky sap can also cause severe inflammation. Collected July 28, 1806, along the Yellowstone River and in what is now Rosebud County, Montana. A newly discovered species.